The future of growth: “All of us, rationally speaking, can be optimistic”

Overview:

- Those in business today have every reason to be optimistic about the potential for growth going forward

- Despite the megacycle of growth coming to an end in the West, those in business will prosper because of market opportunities found in 3 billion people in the developing world moving from poverty to middle class

- A Western consumer market of 500 million baby boomers with time and lots of money to spend, along with the transition to a ‘green’ economy, will provide additional sources for economic growth

- Much more human capital, with education and ingenuity, will provide innovation potential than ever before

- Markets poised for growth in the future include healthcare, big data, and smart materials.

5th article in Afera’s Sicily conference presentation series

Marc de Vos’ presentation “The Future of Growth” was one of the two highest-rated items at Afera’s Annual Conference 2013 in Sicily. Mr. De Vos is currently Director of the Itinera Institute, a Belgian think tank which formulates recommendations for structural policy reforms, with a focus on sustainable economic growth and social protection. A returning speaker by popular demand, he updated the audience of tape producers, suppliers and those in other related businesses on his interesting perspective on the extent and locations of growth in the future.

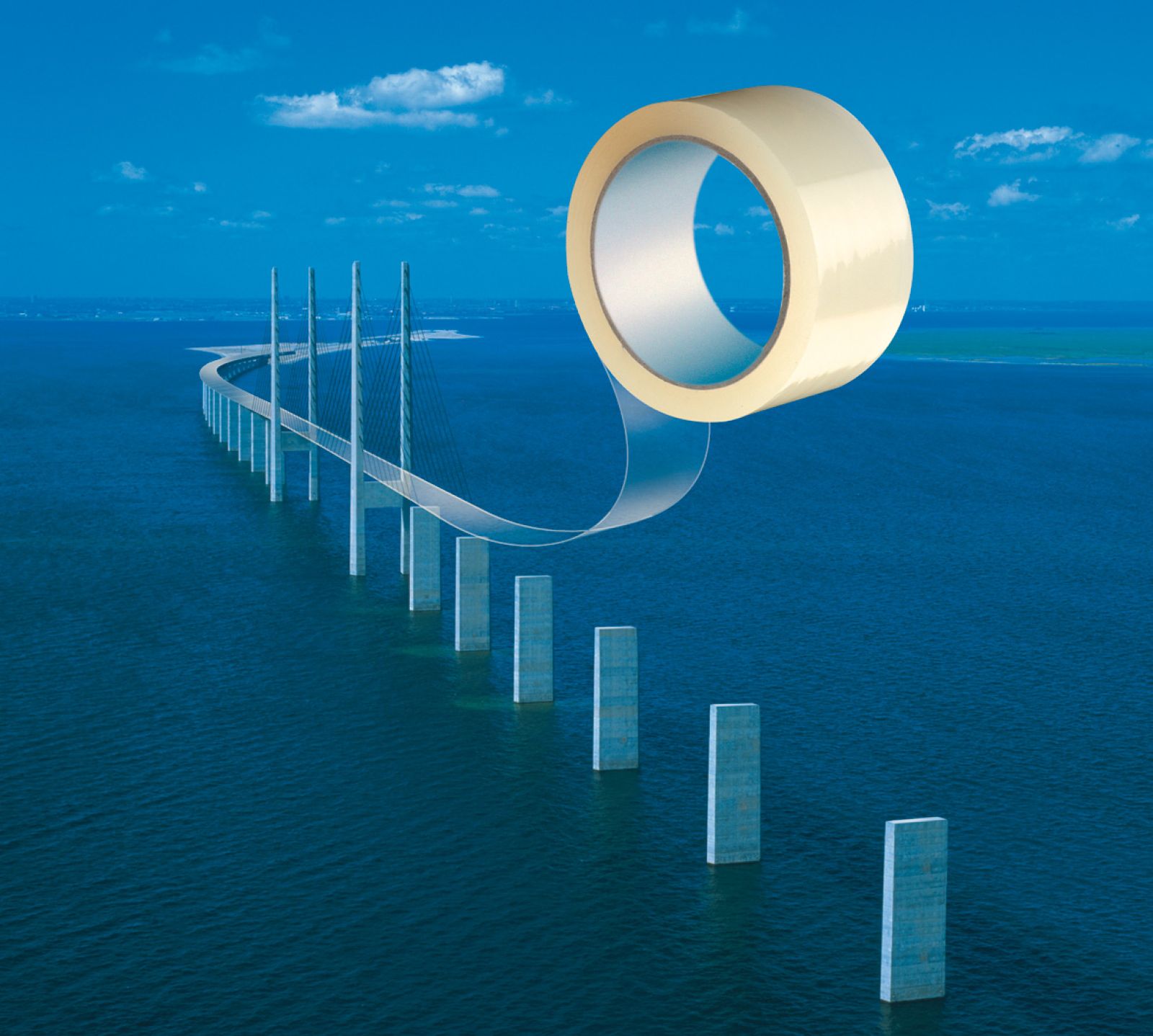

The bottom line: Everyone in business today has every reason to be optimistic about growth going forward. The megacycle of growth in the West may have come to an end, but business will not make a u-turn – it will simply make a turn toward developing countries, Western baby boomers, and the ‘greening’ of the economy.

Prosperity is the rule, not the exception

Despite rampant pessimism, everyone in business today has every reason to feel optimistic about the future potential for growth. Mr. De Vos explained that for more than a century, various field specialists, including economists, heavily underestimated future potential. Bill Gates, for example, said in 1981 that "640K ought to be enough for anybody." Like Gates, we are much more likely to underestimate than overestimate what the future will bring us in terms of innovation and prosperity. The most important lesson we can take away from this discussion, said Mr. De Vos, is that “all of us in this room, rationally speaking, can be optimistic.”

The holy grail of economic policy

The rule of human existence in a historical perspective was not prosperity but stagnation. That rule was broken as of the mid-19th century with the onset of the Industrial Revolution in the U.K. and the rise of capitalism. Growth followed as a natural consequence of:

- individual property ownership, which encourages investment, a work ethic and the rule of law

- a market system of competition (an institutional framework), which is a driver for perpetual innovation, which leads to productivity, which leads to growth

- human capital, i.e., people who want to and do work hard, a.k.a. ‘the spirit of capitalism’, which is composed of motivation, hard work, investment and delay of gratification.

These three items together created a growth chart ‘taking off to the moon and beyond the stars,’ according to Mr. De Vos. Revolution is the marriage of scientific innovation with market developments and capitalism.

Will growth last?

Some say it’s over

In the current period of economic change – post-crisis trauma – so many learned minds are saying ‘it’s over’, ‘forget it’, ‘it’s not going to be like it used to be.’

They believe that what we’ve done since the first Industrial Revolution is pick low-hanging fruit. Since this is now gone, it’s going to become ever more difficult to create new prosperity. In the West, the population is ageing. Mr. De Vos says “we had a demographic sweet spot, and it’s over.” Secondly, women entered the economy, creating an engine for new capital. Room in the labour force is much more limited than it used to be. Thirdly, we have experienced an education revolution, in which 30-40% of people in the West have university degrees. We are close to the limit of using education as a kind of dynamo to get more out of human capital. Finally, the work ethic – the spirit of capitalism – has diminished, because people are working less, consuming more and over-indebted.

In another argument against growth in the future, experts point out that the rate of innovation is slowing. What started as an avalanche of dramatic breakthroughs in the 1950s is now merely incremental improvement. We are not living in outer space with flying cars and robot maids like in “The Jetsons”, but we have the iPad. We’ve used the monetary stimulus of debt – 35 years of debt addiction, to be precise – to hide the slowing rate of innovation.

Institutions hamper innovation, must be governed to promote growth and equality

Mr. De Vos believes the key lies in structured institutions: markets, property, rule of law, government. Our economy has changed from manufacturing to services. An important challenge is to find the service jobs which will drive innovation. An increasingly bigger slice of the economic pie is subjected less to market forces stimulating innovation in the present than it was in the past. We all know that many service jobs now are government determined. Government is not the engine for economic innovation.

In many more countries, millions of civil servants – bureaucrats – work in government healthcare systems, yet innovation certainly lies in healthcare and everything surrounding health. The problem is how to translate that innovation into economic growth, when the government is supposed to pay for it. The growth of expenditure linked to innovation in healthcare is twice the average growth of the economy in the West on average in the past 40 years. According to Mr. De Vos, if your government is spending 10% of tax income on healthcare today, you will spend 20-30% - even more – of your tax income on healthcare in the future. Raising taxes to pay for this would kill the economy.

The lesson: When the potential for growth is under the umbrella of the government, you must realise that this potential is a threat to the economy, because you need more tax income. You’re stuck. Innovation lies with the consumer. It’s bottom up, doesn’t fit with the system. It cannot be encased by a lot of structures if you want it to progress. It is structures such as governments which are holding back innovation and productivity. What is the platform for innovation then? This is a politically difficult, institutional question, which has become a global one.

Technology has done away with many clerical jobs. It has, however, raised productivity and lowered opportunity costs for everyone. Technology has made the successful more successful, so growth is no longer shared, it is concentrated.

Globalisation

Globalisation is having a huge affect on innovation. Approximately 1.3 billion people are entering the labour force in the global market, and Mr. De Vos points out that these make up cheap labour.

Innovation is characterised by cycles in change and supply. Innovation occurs in processes – so it’s not necessarily about what you do, but how and where you do it. iPads and iPhones are designed by Apple in the U.S. but made on the manufacturing floors of Foxconn in Asia, Eastern Europe and Latin America. This scheme is very effective and inexpensive, and the profits go to those based in the U.S. No one produces anything anymore in the U.S. Globalisation has benefitted everyone, but for the West, the innovation drive has become directed towards exporting globalisation rather than creating new stuff. If you don’t do this, says Mr. De Vos, your competition will, and you will die.

Humanity has survived for thousands of years without growth. Why wouldn’t we be able to manage with a little bit less growth than we have in the past? Why couldn’t we have prosperity without growth? Mr. De Vos believes that we need growth more in the future than we do today in order to pay off the last 40 years of debt – gradually – somehow. In addition to this, in the West there is a cohort of about 135 million baby boomers that are set to retire. Many promises have been made to this generation that weren’t financed upfront. Thus the only way to pay for them is through growth.

The confidence factors: “The opportunities are huge – unbelievable!”

Despite these challenges, Mr. De Vos believes that we will manage, although it may not be easy. In fact, he says, the future has almost never looked this bright in terms of economic opportunity. Why? These points are critical to understanding growth in the future:

- Be rationally optimistic about humanity’s innate potential to surprise itself positively. We are very likely to be surprised positively by what Donald Rumsfeld termed ‘the unknown unknowns’, i.e., future innovations. If we go back through history, we can be reasonably optimistic about ourselves. Humanity is a mess – it always has been – but somehow, somewhere, we always manage to surprise ourselves.

- Do not exaggerate the crisis we are in. Other crises, such as World War I, The Great Depression and World War II, which were a bit more challenging than ours today, had an extremely limited impact on the overall growth trajectory. In the big picture, the post-crisis trauma we are experiencing in just a glitch.

- The single biggest economic growth opportunity ever is before us. It is a known unknown that analysis of the growing developing countries, including their demographic and economic trajectories, which may be somewhat bumpy, shows positive results overall. In the next few decades, approximately 3 billion people will join the global middle class – 1 billion is joining very quickly already, with 2 billion to follow. The Golden Sixties included a market of about 300 million people. The economic opportunity ahead of us is 10 times larger and moving 5 times faster – thus 50 times that of the Golden Sixties.

- No matter what happens to the economy, a rich, Western consumer market 500 million strong awaits you. The baby boomers, the wealthiest generation ever, have an active lifespan of about 10-15 years before they become dependent on healthcare. In Europe, Japan, the U.S. and Australia, the baby boomers have time and money to spend. If you are in business, Mr. De Vos predicts smooth sailing ahead.

- Don’t underestimate the transition to a ‘greener’ economy. We are becoming greener all the time. Consultants have calculated that the market opportunity in green products and services is on the same scale as the markets for the train, car and PC put together. It involves energy use transversally, across the board, in everything you can think of. That’s a market beyond belief.

- Human capital will be much more important than ever before. There are 3 billion people who are growing out of poverty into middle class. This is 3 billion people who are more educated, are full of ideas, and could potentially produce unknown unknowns. In the future, we are going to be able to utilise much more human capital – thus much more innovation potential – than in the past.

- Key markets include healthcare, big data, and smart materials.

Mr. De Vos says that if the above 7 points don’t make you feel less pessimistic about the future, then you are either not entrepreneurial or in the wrong business. Or perhaps you shouldn’t be in business at all? Notwithstanding huge challenges, economic engines are bigger, stronger and more numerous than we have ever seen. Every new opportunity ahead will have a market that is many times over what it used to be. Finally, the future of growth is the past. It’s going back to the essentials and improving what’s there to work with. Mr. De Vos believes that if you do that, there is plenty of low-hanging fruit ahead.

About Marc de Vos

Prof. Dr. Marc de Vos is currently Director of the Itinera Institute, a Belgian think tank which formulates recommendations for structural policy reforms, with a focus on sustainable economic growth and social protection. He also teaches Belgian, European and international employment and labour law, as well as American law, at Ghent University and the University of Brussels (VUB). He frequently publishes, lectures and debates on issues of labour and employment law, European integration, labour market reform, pensions, healthcare, ageing and the welfare state, both nationally and internationally, and in academic, professional and policy circles, as well as in the media. Mr. De Vos holds a licentiate and doctorate in law from Ghent University, a masters in social law from the Université libre de Bruxelles, and a masters in law from Harvard University.

Questions and Comments?

Marc de Vos

General Director

Itinera Institute VZW-ASBL

marc.devos@itinerainstitute.org

www.itinerainstitute.org

Boulevard Leopold II Laan 184d

1080 Brussels

Belgium

T +32 2 412 02 62

F +32 2 412 02 69